Switzerland still handing out fossil fuel finance like candy

Swiss campaigners asking SERV to stop supporting fossil fuel projects (photo Miriam Kuenzli)

The Clean Energy Transition Partnership (CETP) was one of the most important breakthroughs of the Glasgow climate COP in November 2021. Under the partnership five public finance institutions and 34 countries – including Switzerland – committed to end international public finance for fossil fuels by the end of 2022 and to prioritize finance for clean energy instead.

In a report published in August, the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) found that in 2023, international public fossil fuel finance from the original signatories had decreased by up to two thirds, compared with the 2019-2021 average. Such finance still amounted to $5.2 billion in 2023 however.

The IISD report found that Switzerland was one of five countries which violated their commitments to the CETP in 2023, along with the United States, Italy, Germany and the Netherlands. As the report’s Figure 3 below indicates, Switzerland is the only country which significantly increased its fossil fuel finance after the CETP entered into effect.

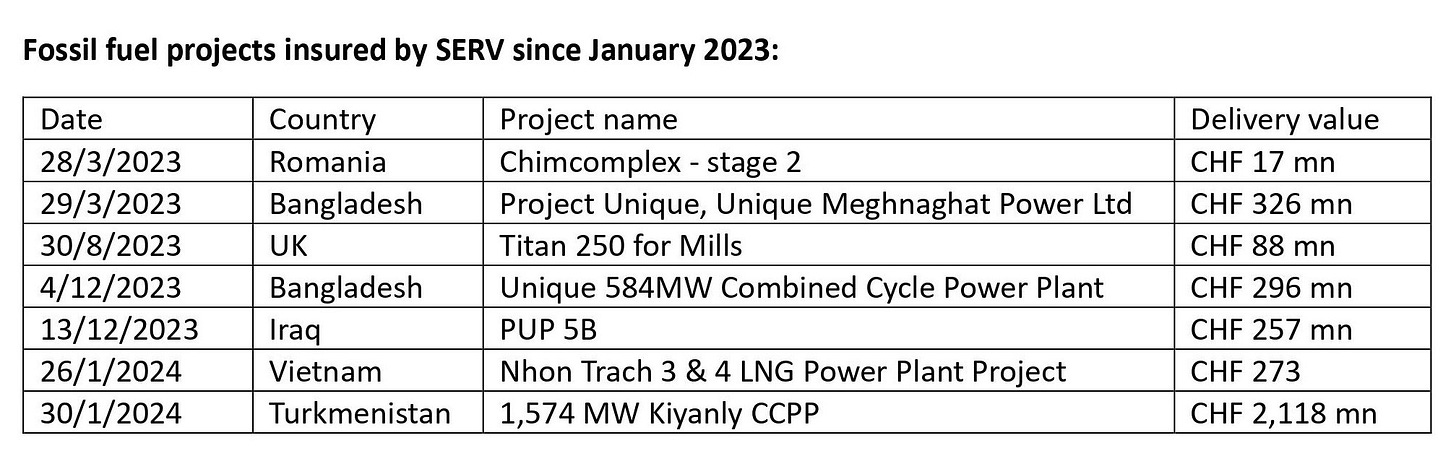

According to its own website, the Swiss government’s export risk insurance agency SERV has approved insurance for six gas projects with a total delivery value of CHF 3,375 million (or USD 3,967 million at the current exchange rate) since the CETP took effect. The fossil fuel projects which SERV insured in 2023 and 2024 are listed in the following table. (Their delivery value may be larger than the value insured by SERV.)

Switzerland is also the only country which has explicitly weakened its CETP policy. In March 2023, SERV pledged to end all its fossil fuel finance, with exemptions only for projects in line with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C goal. In July 2024, Oil Change International (OCI) revealed that the agency had quietly watered down its policy by allowing SERV to fund any gas project it considers is in the “economic, foreign, trade and development policy interests of Switzerland”.

Responding to a question in parliament, the Swiss government argued that “modern gas-fired power plants represent an important transition technology in some cases, and their support can therefore be useful”. Yet the theory of gas as a transition fuel has long been debunked. And as OCI’s Adam McGibbon, a co-author of the new IISD report, comments, “SERV’s loophole is large enough to push any new gas project through it and renders Switzerland’s CETP commitment meaningless”.

By far the biggest new fossil fuel project which SERV approved in violation of the Swiss CETP commitment is a gas-fired power plant of 1,574 megawatt at Kiyanly in Turkmenistan. The large power plant will be built through a turnkey contract by Calik Enerji Swiss AG. SERV approved a project bond insurance for the project in January 2024. Turkmenistan currently generates electricity for domestic use and for export to Iran, Afghanistan and other countries.

This project raises numerous red flags not just in climate, but also in corruption terms.

Red flags on climate…

Two of the main multilateral lenders to Turkmenistan are the Asian Development Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. The first priority in the ADB’s new country partnership strategy for Turkmenistan is to support “the green transition to a sustainable and climate-resilient economy”. The green transition is also one of two “initial focus” areas of the EBRD’s 2019-24 country strategy, given Turkmenistan’s “very high energy and carbon intensity”.

The SERV guarantee for a massive new gas power plant undermines these multilateral priorities. It also seems to be at odds with SERV’s own climate strategy, which is “aimed at promoting climate-friendly projects in foreign trade”. The Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO), which supervises SERV, in turn says that it is “committed to promoting the reduction of greenhouse gases, the adaptation to climate change and the sustainable management of resources in its partner countries.”

… and on corruption

Turkmenistan is reputed to be one of the world’s most corrupt countries. In Transparency International’s 2023 Corruption Perception Index it ranks 170th out of 180 countries, scoring only 18 out of 100 points. In its 2023 Bribery Risk Matrix, the anti-corruption organization TRACE ranked Turkmenistan 193rd out of 194 countries for bribery risks. Crude Accountability called the country “a model kleptocracy” and found that its government “releases no reliable information on economic growth, the national budget, oil and gas revenues, or currency reserves”.

Turkmenistan is also an extremely repressive country. Freedom House in 2020 ranked it second to last among the world’s nations in terms of civil liberties and political rights, above only Syria but just below North Korea. Such an environment breeds cronyism and corruption.

Calik, the Turkish company whose Swiss subsidiary won the turnkey contract to build the Kiyanly power plant, has established a prominent position within this system. The company’s founder Ahmet Calik is not only an old friend of Turkey’s President Erdogan, but also built close relations with Turkmenistan’s long-time Presidents Niyazov and Berdimuhamedow (who handed over power to his son in 2022). Niyazov awarded citizenship to Calik and, according to a leaked cable from the US embassy, made him “his closest business advisor”.

Calik Enerji Swiss is a small outfit, with nine employees according to LinkedIn estimates. Its biggest business focus is on Turkmenistan, where it is well placed to cash in on the prominent position of its parent company. Calik Enerji Swiss doesn’t build the Kiyanly power plant itself but is procuring turbines and generators from GE Switzerland.

SECO states that it “promotes transparent, responsible and efficient framework conditions in its partner countries” and has “zero tolerance for corruption”. Yet Turkmenistan is a member of the constituency which Switzerland represents at the World Bank Group, contributing 0.05% of the votes in the institution. It’s quite possible that SECO applies double standards when applying its good governance principles to the members of the Swiss constituency.

Switzerland’s sorry history with kleptocracies

The Turkmenistan experience recalls Switzerland’s dubious role during President Suharto’s kleptocracy in Indonesia in the 1990s. As I analyzed in a briefing paper in 2000 (which is still available in garbled form here), SERV – in its previous incarnation Exportrisikogarantie (ERG) – offered Indonesian developers guarantees for three coal power plants with a total capacity of 2,406 megawatt from 1992-1996. The power plants were tainted by corruption, overpriced and not needed. Yet when Indonesia’s new democratic government asked the lenders to cancel the illegitimate debts after Suharto’s downfall, ERG and other agencies pressured the government to honor the corrupt contracts.

SERV is not a development or climate agency, but SECO and ultimately the Swiss government need to take responsibility for the coherence of their foreign trade, development and climate policies. The ongoing violation of the Glasgow CETP agreement is a major embarrassment for Switzerland. It confirms the image of a country which signs noble pledges on Sundays and cynically counteracts them on weekdays, which quietly takes away with the left hand what it has proudly given with the right hand.

In a highly critical story on the coal power frenzy under the Suharto regime, the Wall Street Journal in 1999 commented that Western governments were “handing out risk insurance like candy”. Three decades, several climate agreements and a dozen anti-corruption speeches later, Switzerland is still in the habit.

The Swiss government should immediately comply with its pledge under the Clean Energy Transition Partnership and stop offering any international public finance, including SERV guarantees, for fossil fuel projects. Switzerland should also support the adoption of an oil and gas export finance ban at the Export Credits Group of the OECD.

This morning Campax, a Swiss campaign organization on whose board I sit, submitted a petition with 10,000 signatures to SERV asking to agency to end all support for further gas power plants. Swiss NGOs will closely monitor and call out any further Swiss support for international fossil fuel projects.

SERV handing out its own branded chocolates…

Interested in this topic? Subscribe here to receive updates and new posts.